2 November 2023 – 18 February 2024

At the beginning of the 16th century, the Italian Renaissance had reached its high point. It was a time of great cultural production, as Italy’s artists and scholars pursued the ambitious goal of breathing new life into the art and culture of Greek and Roman antiquity. But the Renaissance (meaning “rebirth”) wasn’t just an Italian endeavour. North of the Alps, too, artists, thinkers and rulers were responding to the idea of a new age cast in the mould of a venerable past. Augsburg – city of power, money and the arts – was a centre of the bold new “Renaissance in the North”: The painter Hans Holbein the Elder (1465–1525) and his fellow artists drew on influences from both north and south and developed a distinctive visual language of their own. Their art is representative of a period that would shape northern Europe’s self-image for centuries to come.

Augsburg -

CAPITALISM AND ART

1

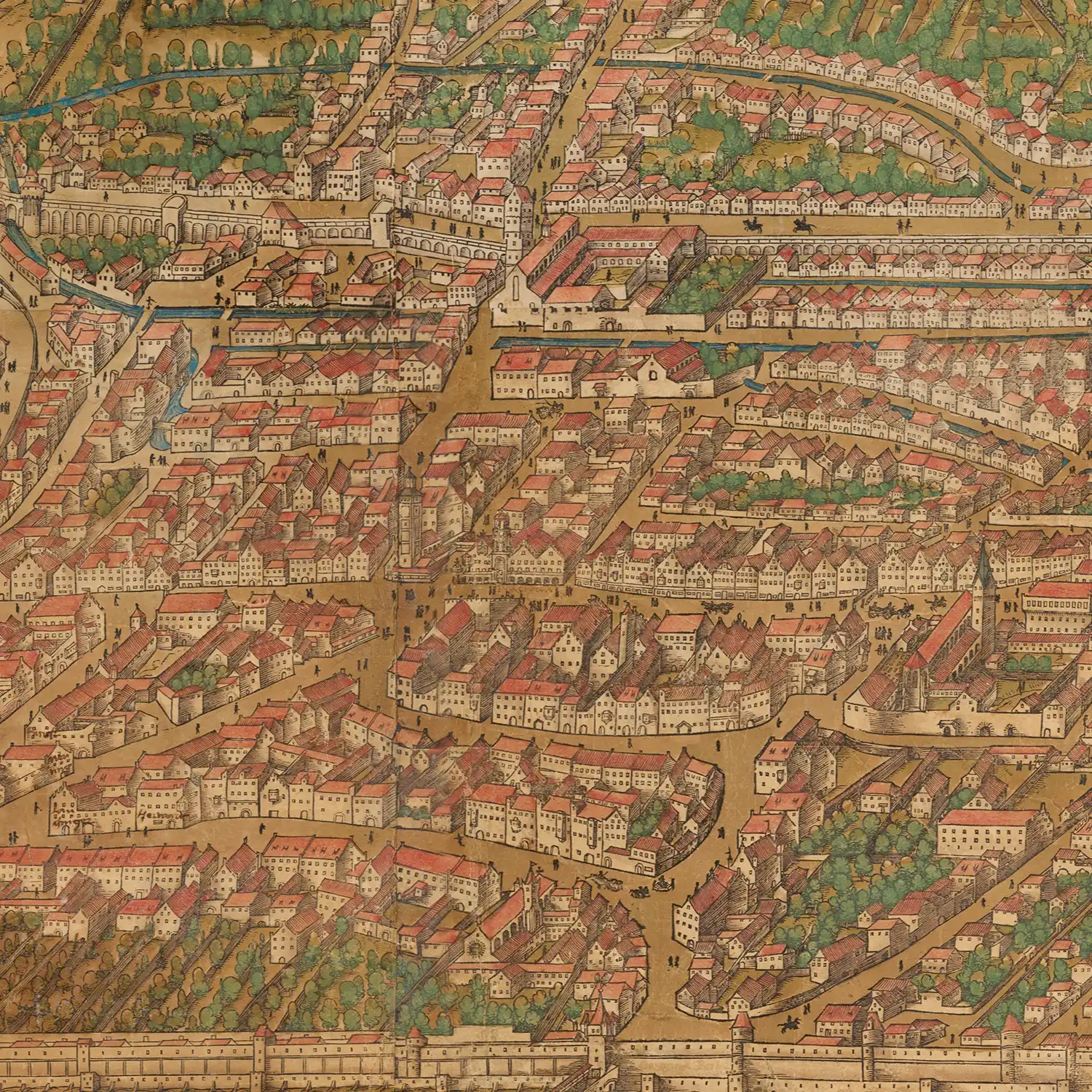

It may be hard to imagine, but in the early 1500s, Augsburg – the picturesque town now overshadowed by its bigger neighbour, Munich – was an important global city in every sense of the word. The city on the Lech was home to globally active enterprises, most notably those of the renowned Fugger dynasty. Emperor Maximilian I (1459–1519), too, was a frequent visitor to the Imperial City.

The city has exceedingly fine houses, wide and clean streets.

WEALTHY, FREE

AUGSBURG

A flourishing hub of trade and culture since the 14th century. Augsburg benefited from its location at the crossroads of ancient trade routes that criss-crossed Europe – from Italy to the port cities on the coasts of the Baltic and the North Sea, and from the Alps to the Atlantic.

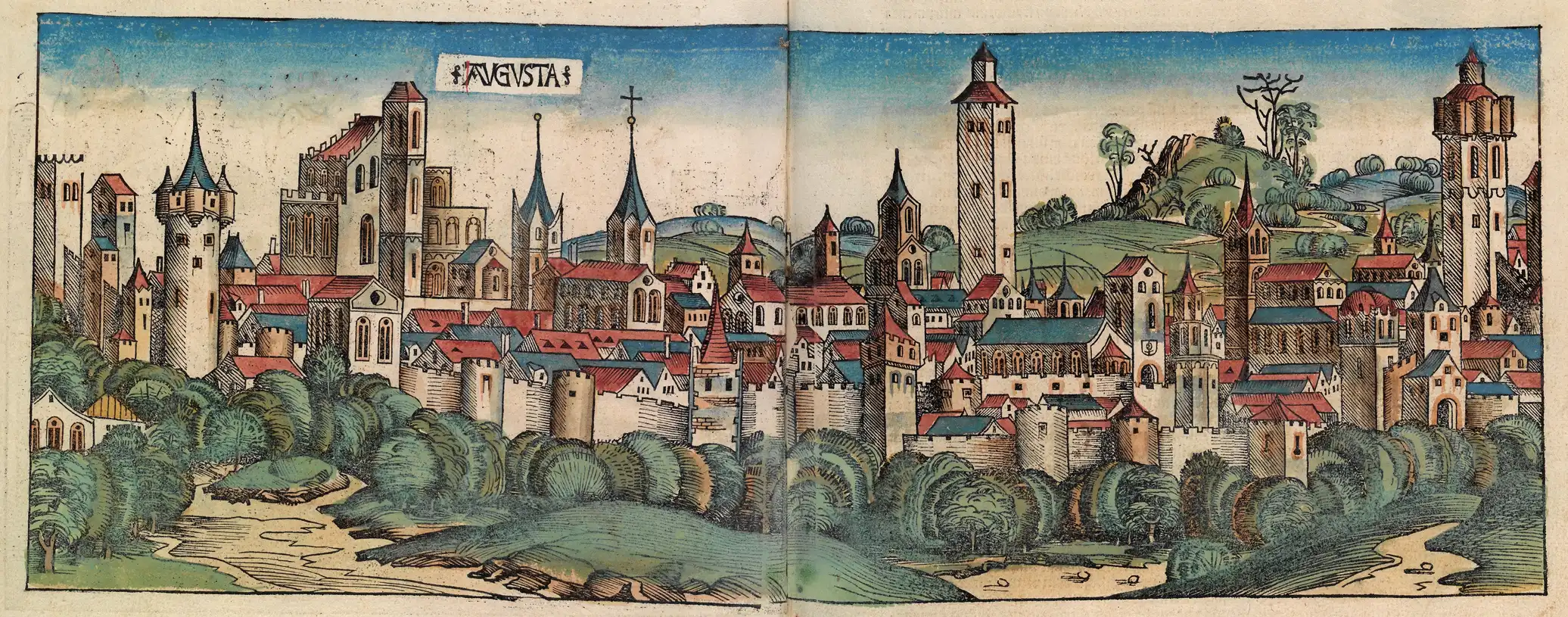

Roman Augsburg

Augsburg is one of the oldest cities in Germany. And around 1500 the citizens of Augsburg were already pondering and studying their classical heritage. As the city expanded, evidence of its Roman past kept coming to light. Probably founded around 8 BC as a legionary settlement under Emperor Augustus, “Augusta Vindelicum”, as it was then known, became the capital of the province of Rhaetia and was situated not far from the Limes, the northern perimeter of the Roman Empire between the Rhine and the Danube.

An Imperial City: around 1500 Augsburg was not ruled by princes or bishops, but by a small city elite that was subject solely to the Holy Roman Emperor himself. As the site of Imperial Diets, the most important political summits of the time, the city regularly hosted prominent international visitors. In Augsburg, those who prospered and attained wealth enjoyed a life of considerable comfort.

What was the source of Augsburg’s prosperity? Around 1500, it was mainly the cloth trade and the coal and steel industries that drove the city’s economic success. The banking and merchant families of the Fuggers and Welsers were some of the richest people in Europe and, as global investors, they put their money to work. For example, through their operations in Venice, their trade connections reached as far as the Levant and India. From the ports of Spain and Portugal, Augsburg ships took part in the expeditions of conquest during the early years of transatlantic colonial expansion. Beneath all the finery, there was a darker side to the bankers’ wealth.

Power and Brutal Oppression

The period of the “Renaissance in the North” marks the beginning of modern European efforts to achieve world hegemony. The colonial subjugation of people and countries was fuelled by a highly questionable sense of cultural superiority. The Fuggers and Welsers duly participated in the emerging trade of enslaved people from Africa. The Fuggers used their mines to produce manillas – metal objects of exchange that have gone down in history as a “slave trade currency” due to their use on the coasts of West Africa. The Welsers, in turn, attempted to establish a colony in what is now Venezuela and shipped more than 1,000 enslaved Africans to America. Meanwhile, in the homes of prosperous Augsburg citizens, enslaved people from India were forced to toil for their “masters”.

In terms of craftsmanship and artistic ingenuity, Augsburg was a proud rival to Italian cities. Following the example of Italian centres of the Renaissance, such as Padua, Bologna, Venice and Florence, Augsburg’s civic society strove for technical and artistic innovation.

Ne Italo cedere videamur

(„Lest we be seen to cede to Italy.“)

Exploring the culture of antiquity and revitalising its splendour – that was a guiding principle of the Italian Renaissance. In Augsburg, too, efforts were made to revive the distant past and to study the vestiges of Roman art in the city. At the same time, the Augsburg masters knew that merely aping achievements already made on the other side of the Alps wasn’t going to be good enough. To be true artists, they had to achieve their own cultural “rebirth” and usher in a “Renaissance in the North”.

Humanism and Renaissance

Renaissance humanism (from humanitas – Latin for that which distinguishes man) was a cultural movement that originated in Padua and Tuscany in the 14th century. The Italian poet Petrarch (Francesco Petrarca, 1304–1374), dubbed the father of humanism, encouraged the study of pagan civilizations and the teaching of classical virtues and was instrumental in the dissemination of the movement throughout Europe. Humanism promoted the idea that cultural renewal could be achieved through a “return to the ancients” and the study of the legacy of antiquity. Ancient Roman Latin, modelled on the writings of Cicero (106–43 BC), replaced medieval Latin as the scholarly language of Europe. Petrarch also formulated the goal of forging a new age of light to dispel the “darkness” that supposedly characterised the Middle Ages – still often referred to as the “Dark Ages”. Today we know that several “renaissances” – that is, several periods that sought to revive classical literature, art and philosophy – punctuated the European Middle Ages, for example in the time of Charlemagne (747–814) or Frederick II (1194–1250). Renaissance humanism focused on the individual, the individual’s capacity to engage in civic life, and conceived of the ideal citizen as self-confident, creative, educated and virtuous.

PICTURES

FOR ETERNITY

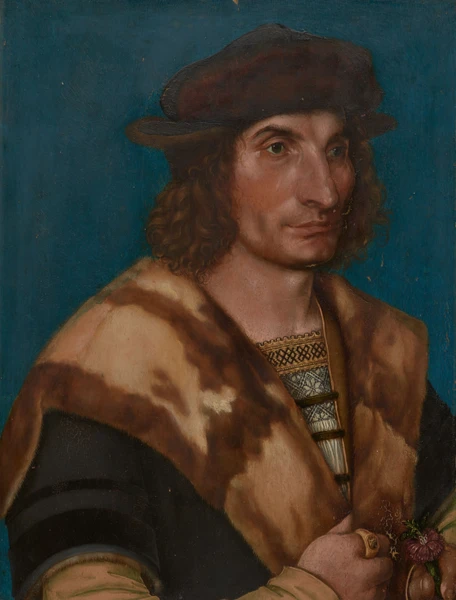

As the ideas of humanism and the Renaissance took hold, Europe saw a growing demand for portraits. Spurred by their sense of individual importance and financial power, Augsburg’s city elite had themselves immortalised in pictorial form. Hans Holbein the Elder and Hans Burgkmair the Elder were among the leading portraitists of the early 16th century and shaped the visual language of the “Renaissance in the North”.

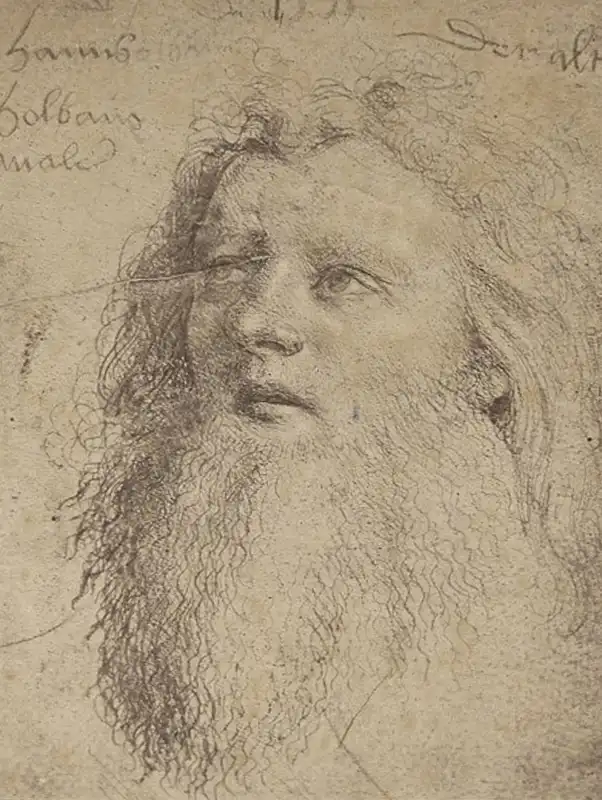

HANS HOLBEIN THE ELDER

Hans Holbein the Elder certainly knew how to make an impression: His self-portrait with wild hair and a big bushy beard shows a man as eccentric as he is memorable. Born in Augsburg, he was the progenitor of a dynasty of painters.

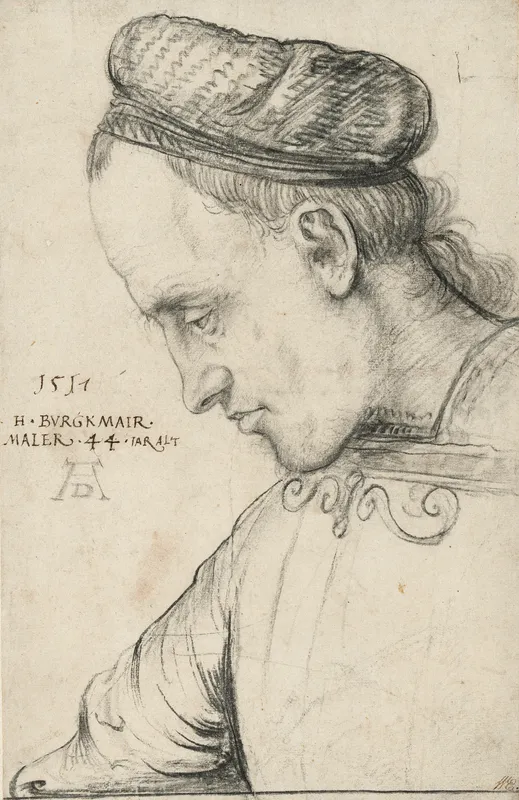

HANS BURGKMAIR THE ELDER

Self-confident and focused – this is how Hans Burgkmair the Elder presents himself in this drawing. Although largely unknown today, he was one of the most influential artists in northern Europe and one of the court artists of Emperor Maximilian I.

Although possessing very different artistic temperaments, Hans Holbein the Elder and Hans Burgkmair the Elder enjoyed equal success with their portraits of Augsburg’s mercantile and patrician elite. Their portraits exemplify what distinguished the Northern Renaissance: the mixture of northern European – Netherlandish and German – traditions and the visual language of the Italian Renaissance with its references to classical antiquity.

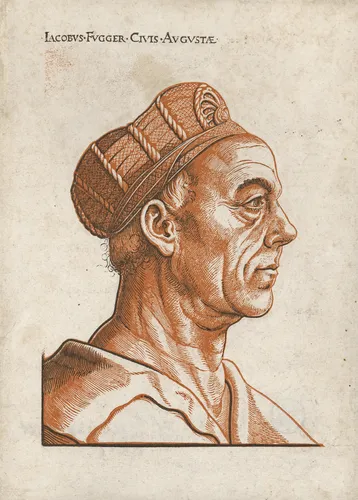

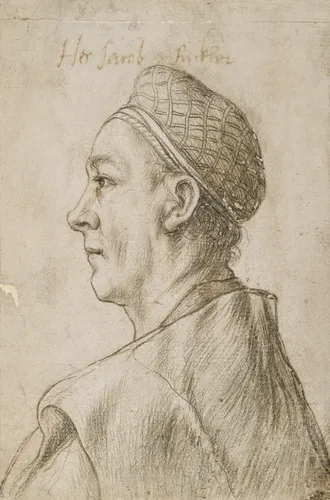

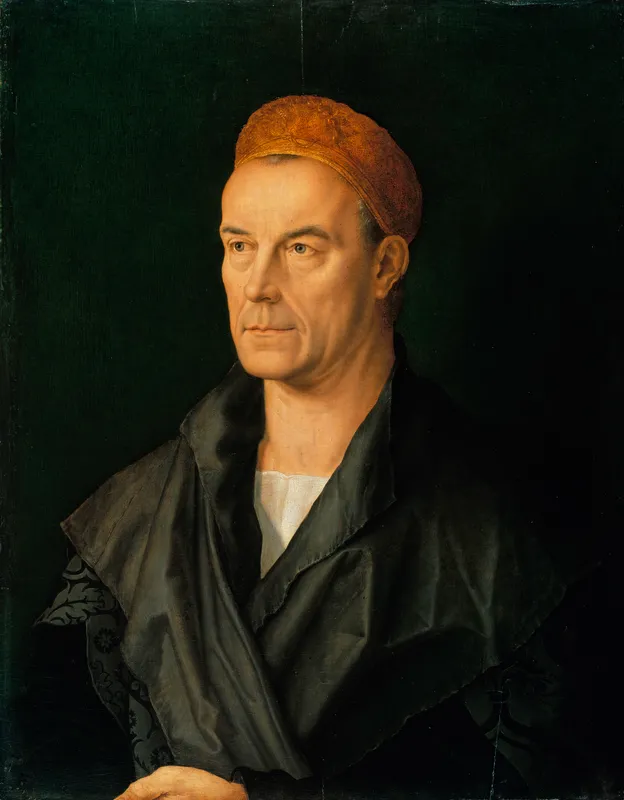

Jakob Fugger, the richest man in the world at that time, as portrayed at the Augsburg Imperial Diet in 1518 by Albrecht Dürer, an artist as celebrated in his metier as the banker was in the world of commerce. Based in Augsburg, the head of the Fugger family ruled over a far-reaching business empire built primarily on the cloth industry, mining and metal processing. Only emperors and princes had their portraits painted as often as this powerful banker and merchant.

Anticipating the sense of mission that seems to drive some of today’s super-rich individuals, Jakob Fugger used the latest media of his time for flagrant self-promotion. Whether on medals made of precious metals or on inexpensive prints – a mass medium that was taking the world by storm – the face of the entrepreneur was everywhere.

Hans Holbein the Elder and Hans Burgkmair the Elder were just two of many artists commissioned to paint Jakob Fugger. The merchant pursued a consistent strategy to promote his image: every portrait had to be instantly recognisable. The distinctive eyebrows and the costly reticulated cap were integral to the businessman’s “signature look”.

One might be forgiven for suspecting a note of satire in this small wooden relief: In a magnificent palatial setting, the personifications of Power and Wealth dressed in classical robes pay homage to Jakob Fugger. But there is more than meets the eye in the seemingly hubristic depiction of the bourgeois merchant sitting on the imperial throne. With his immense fortune, Jakob Fugger bank-rolled Emperor Maximilian I, who was perpetually burdened with enormous debts. Thus, the Fugger city of Augsburg became the financial capital of the empire, the “Wall Street” of Maximilian’s time.

Maximilian und die Schulden

When Emperor Maximilian I died in 1519, he left behind a huge mountain of debt. He owed vast sums to the Fugger Bank in Augsburg. His successor Charles V (1500–1558) had to ask for debt relief. Centuries later, the history painter Carl Ludwig Friedrich Becker (1820–1900) imagined the burning of the promissory notes in the fireplace as a consensual meeting of money and politics, with Fugger granting the new emperor a proverbial “haircut”. However, in reality, negotiations had been extremely tough: Charles V was forced to abandon his plans for an “imperial monopoly law” that would have massively curtailed the scope of action of the banking and trading houses in the Holy Roman Empire.

Maximilian -

THE MEDIA-SAVVY

EMPEROR

2

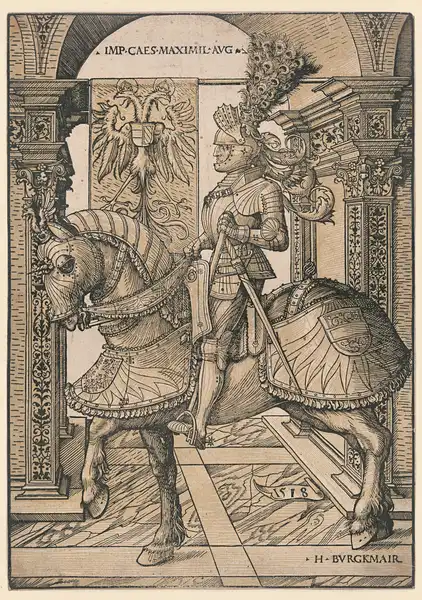

Maximilian I relied on the power of images. In declaring the emperor’s personal power and his rule, Augsburg advisers and artists kept coming up with new visual campaigns, thereby shaping the “Renaissance in the North” in their own distinctive way.

THE EMPEROR,

HOLDING THE REINS?

To this day, Maximilian I is a celebrated historical figure in Austria and Bavaria and the subject of numerous myths. However, under his rule the Holy Roman Empire (or “Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation”, to use its full title) remained difficult to govern. This made it all the more important for the emperor to pursue a multimedia image-building campaign – his image was supposed to hold the empire together.

An Unruly Empire

Maximilian I was born Archduke of Austria in 1459, ruled the Holy Roman Empire, first as king from 1486, before being officially elected emperor in 1508. But his realm consisted of a sprawling panoply of scattered territories. While other major European powers, such as France and England, were becoming increasingly centralised, the “King of the Germans” faced wave after wave of resistance from territorial princes. His reforms were difficult to implement. The threat posed by the powerful Ottoman Empire in the east also remained a major concern. In an age of mercenary armies, Maximilian’s determination to expand and defend his realm gave rise to a permanent and severe shortage of funds. During the Italian Wars, the Augsburg banking houses of the Fugger and Welser families are believed to have lent him 12 tons of gold for the Siege of Padua (1509) alone.

Maximilian, “The mayor of Augsburg”

Maximilian I made no secret of his affection for the Imperial City of Augsburg and its citizens and spent a great deal of time there. This was not lost on the French court, where it earned him the derisive nickname of “Mayor of Augsburg”. It was not only the art, the new printing technology and the substantial loans that drew the emperor to the city on the Lech. Augsburg organised the Imperial Diets, safeguarded documents and valuables, and supplied weapons of war – in other words, it was an important pillar for the day-to-day functioning of Maximilian’s rule across the entire empire.

Dem Ruhm des letzten Ritters, den eine Kron' geschmückt,

Dem Ruhm des letzten Fürsten, den Rittersinn beglück.(“To the glory of the last knight adorned with a crown,

To the glory of the last prince favoured with chivalry.”)

Cultivating a public image doesn’t happen overnight – it takes years of strategic planning. Maximilian I adopted a range of different roles for his appearance in different media. Not only did he know how to present himself as an approachable, personable emperor, he also played the role of a chivalric, conquering hero. “Emperor Maximilian – the last knight” – that reputation continues to follow him to this day.

A knight needs armour: this suit of field armour was made for the 25-year-old Maximilian by Lorenz Helmschmid, an armourer from Augsburg whose work was in demand throughout Europe. A superbly crafted suit full of nostalgia: the long, pointed iron foot defences and fine ornamentation that distinguish the armour celebrate the chivalric fashion of the Middle Ages that was already waning around 1500.

DAS ERBE VON BURGUND

Pointy shoes and chivalric splendour – Maximilian’s contemporaries would inevitably have associated these things with the courtly culture of Burgundy. In addition to the Duchy of Burgundy and the Franche-Compté, the once-great power also included the flourishing Burgundian Netherlands. Thanks to his marriage to Mary of Burgundy, the daughter and heir presumptive of the legendary Burgundian duke Charles the Bold, Maximilian became ruler of this vast and wealthy domain in 1477. But Mary died young in 1482 as the result of a riding accident, and France waged war to bring the core Burgundian territories back under its control. Maximilian and the House of Habsburg retained control over the financially strong Netherlands. This made it all the more important for Maximilian to make the Burgundian heritage an integral part of his image.

THE EMPEROR’S

ARTISTS

Maximilian I’s propagandistic image campaigns around 1500 were unprecedented: with the help of advisers and artists, the emperor carefully constructed a “virtual” public image. The stories and pictures about his ancestors, his personality and his empire oscillate between fiction and reality.

Making one’s private life public, publicising one’s life story: What has now become standard practice in the digital age was unheard of in Emperor Maximilian’s time, and was only made possible through the brand-new mass media of printed books and images.

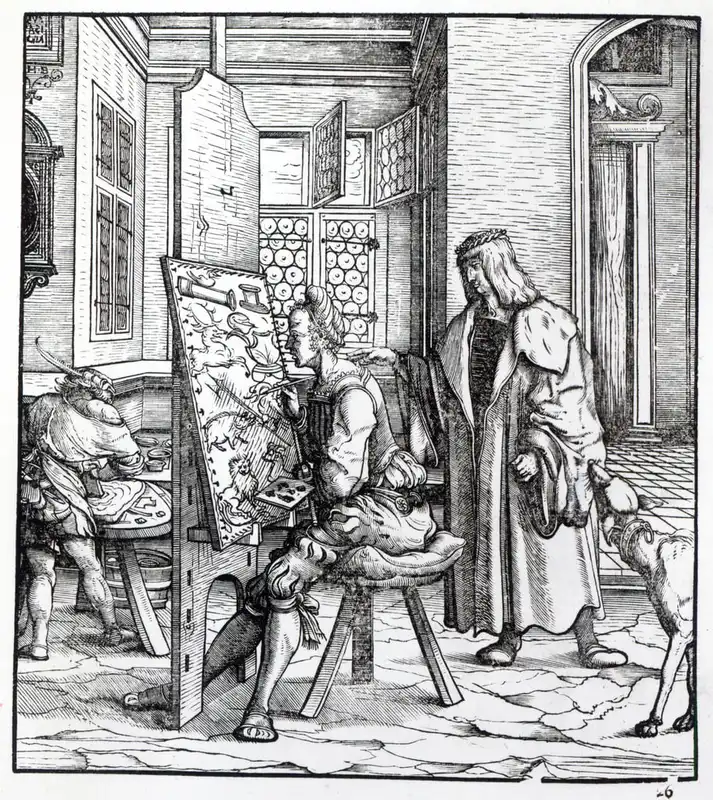

An informal, almost cosy scene: the emperor himself is looking over the artist’s shoulder as he works at the easel – did this really happen? With this print, Hans Burgkmair the Elder not only presented his patron in a favourable light, he also created a remarkable self-portrait.

The scene in the artist’s studio is taken from the book Der Weisskunig. Eine Erzählung von den Thaten Kaiser Maximilians des Ersten (The White King: A Tale of the Deeds of Emperor Maximilian the First), one of the emperor’s ambitious autobiographical projects. A total of 250 such woodcuts were to illustrate the biography. The emperor himself referred to the Weisskunig and similar publicity ventures as “commemorative” works, in his own memory – even though he was still very much alive.

He who does not ensure his remembrance in his lifetime will be forgotten after his death [...] and that is why the money I spend on my remembrance is not wasted.

Legendary Maximilian

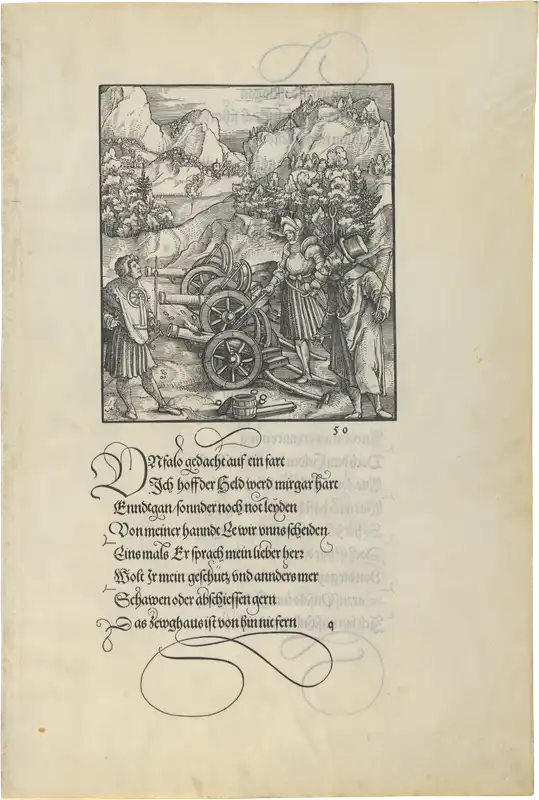

Further to Weisskunig, Theuerdank was another of Maximilian’s “commemorative” projects. Here the emperor appears in the form of a youthful hero on a journey to wed his promised bride. He has daring adventures in wars, hunts, and tournaments and cuts a splendid figure at various courtly festivities. The poem, which is cast in the mould of a medieval heroic epic, draws on actual events in Maximilian’s life. Illustrated with 118 woodcuts, the book was first published in Augsburg in 1517. The new technique of letterpress printing allowed for sizeable editions and gave the emperor hope of broadcasting his legendary image as a man of great valour and prudence throughout the empire.

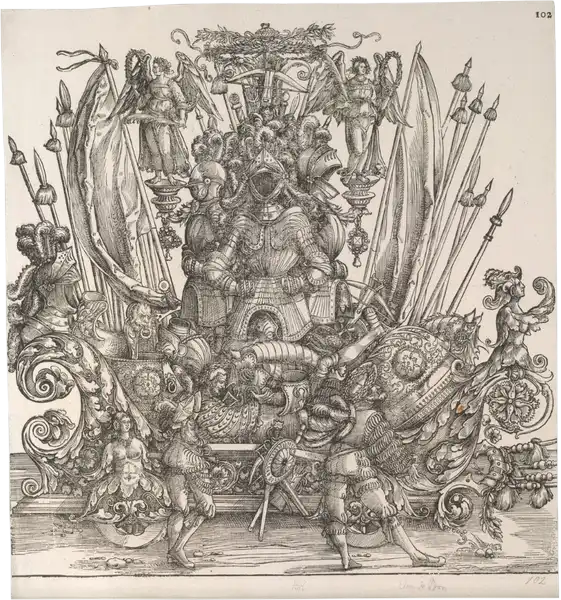

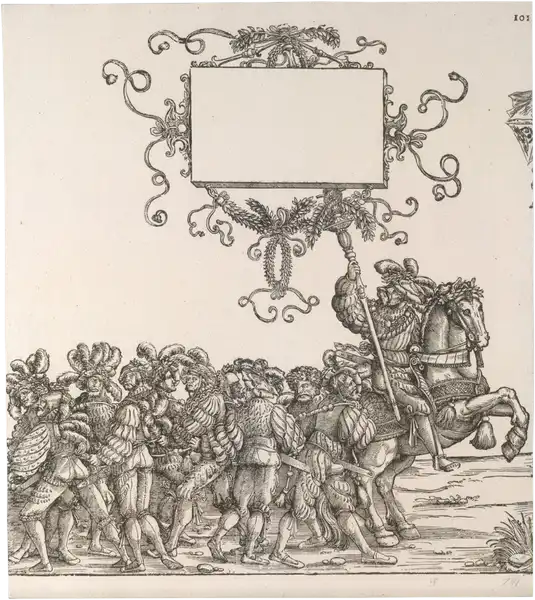

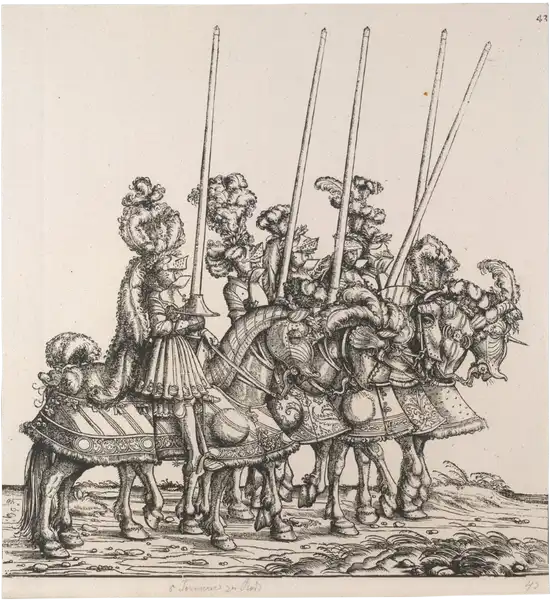

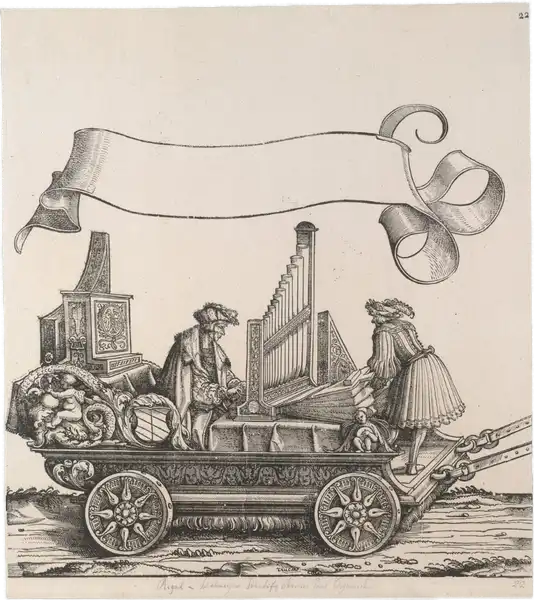

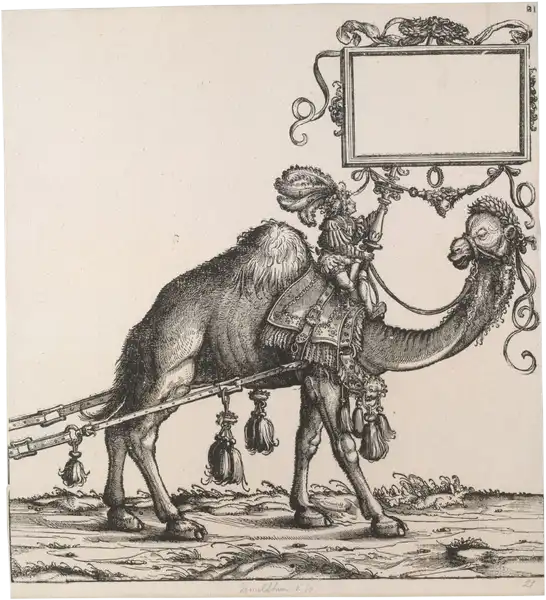

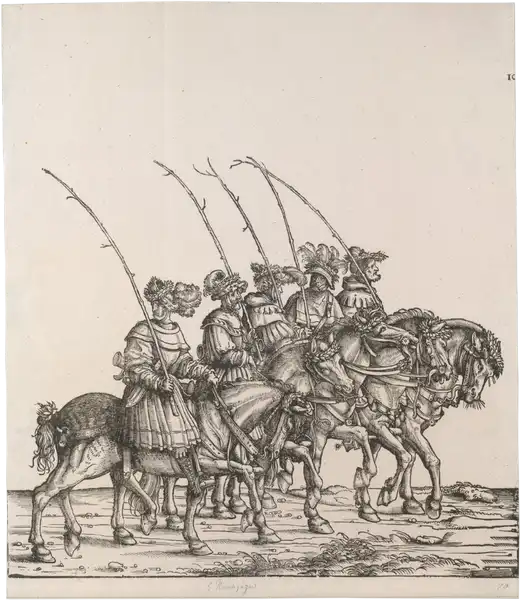

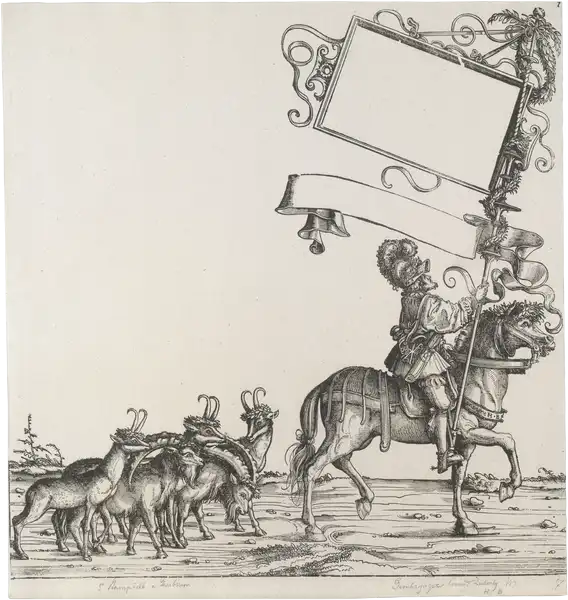

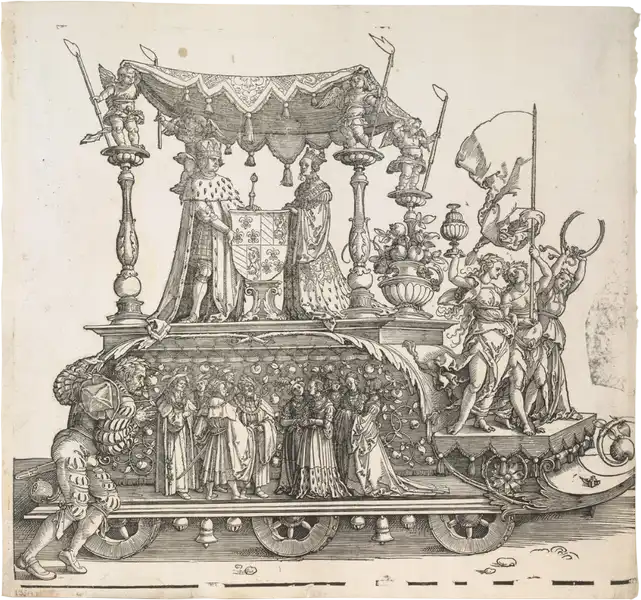

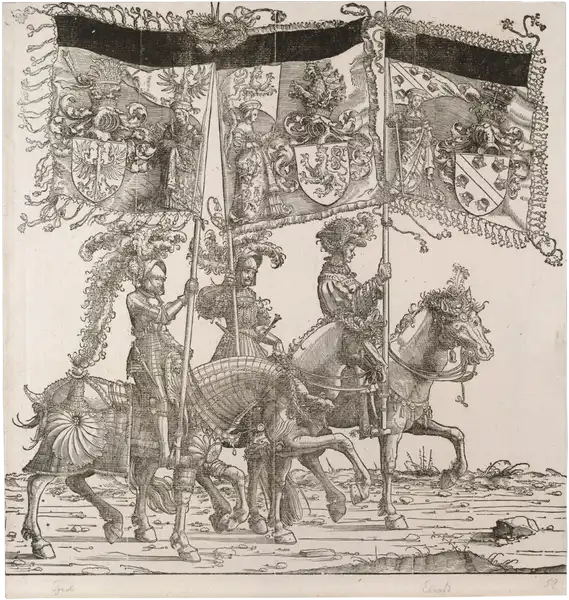

Chivalric images and tales of heroism were not enough for Maximilian. Radical and creative in equal manner, the media-savvy emperor exploited the propagandistic possibilities of the print medium to the full. The Triumphal Procession is one of the most astonishing programmatic series of images of the “Renaissance in the North”.

Triumphal Poster Wall

Approximately 54 metres long! The Triumphal Procession encompasses a total of 137 woodcuts. The prints were probably intended to adorn the walls of council chambers and palace halls throughout the Holy Roman Empire. A virtual triumphal entry of the emperor that never actually occurred in real life. Who wouldn’t have been left speechless by this new use of the print medium? But, like many of Maximilian’s overly ambitious image-building projects, the Triumphal Procession remained unfinished.

Modelled on Roman triumphal processions and peppered with forms and figures from antiquity: Maximilian’s Triumphal Procession follows the Italian Renaissance. And yet the work strikes a distinctly Northern tone. Not painted, but printed as a series of woodcuts (an orginally Northern technique), with sinuous, curved lines. An abundance of detail, copious hunting and forest imagery, as well as armour and fashions in the grand chivalric tradition delineate the distinctive characteristics of the Northern Renaissance in Maximilian’s Holy Roman Empire.

Quest for the Past

Genealogical research and amateur archaeology: Maximilian I, too, took a keen interest in these pursuits and enlisted the services of the Augsburg humanist Konrad Peutinger to advise him. Whether it involved compiling or rather fabricating genealogies all the way back to ancient Troy or excavating what were supposed to be the bones of the hero Siegfried from the Nibelungenlied (or Song of the Nibelungs), more often than not, the view of the past had nothing to do with reality. The interest in origins and primeval times served the quest for and formation of a distinctly Northern cultural identity.

NORTH AND SOUTH –

LANGUAGES OF ART

3

City of money – city of the emperor – city of the arts: In Augsburg, painters and printmakers experimented with influences from northern and southern Europe. While Italian artists sought to revive Roman antiquity in cities that lay on former Roman territory, their northern European colleagues, living largely outside the borders of the ancient Roman empire, started searching for their own origin myths.

A Bit of Both!

Augsburg’s cultural and artistic production was booming. Hans Holbein the Elder and Hans Burgkmair the Elder combined Netherlandish and Italian influences to create a new visual language that characterises the “Renaissance in the North”.

Hans Holbein’s The Fountain of Life demonstrates the mixture of Netherlandish and Italian forms particularly clearly. Painted in 1519, the year of Emperor Maximilian’s death, the enigmatic masterpiece continues to present art historians with riddles.

What Hans Holbein the Elder did in painting, Hans Burgkmair the Elder did predominantly in printmaking. Like his colleague, he didn’t simply copy the forms of the Italian Renaissance, but adapted them and made them his own.

THE FOREIGN AND

INTRINSICALLY GERMAN

The culture of Roman antiquity and the ambition to create something new: Augsburg’s artists and intellectuals measured themselves against the recent achievements of the Italian Renaissance. At the same time, they increasingly felt the need to define their own strengths and build on the origins and traditions particular to the north.

There is almost no nation [in Europe] that does not love to boast of an origin that lies far back or far away.

“German” and “welsch” – to use the Middle High German word for “foreign” or “southern”, specifically Italian. Around 1500, humanists began to discuss the cultural differences between the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation and Italy. The debate also found expression in art. In Augsburg’s famous Fugger Chapel, Northern and Southern forms are purposely combined and contrasted. The funeral chapel was built between 1509 and 1512 in the Augsburg church of Saint Anne – a gesamtkunstwerk commissioned by Jakob Fugger.

Jakob Fugger had a great desire to build […]. Thus he redesigned the Fugger funeral chapel at great expense and in the most exquisite manner, with gold, silver and fine wood in the Italian style.

Fugger’s contemporaries already marvelled at the fine materials and the “welsch” (i.e. Italian) style, of the Fugger Chapel. Others saw the Italian influence as an entirely unnecessary and ostentatious affectation of the super-rich. Time and again, an allegedly Italian hedonism was decried as the antithesis of the supposedly German virtues of down-to-earth modesty and simplicity.

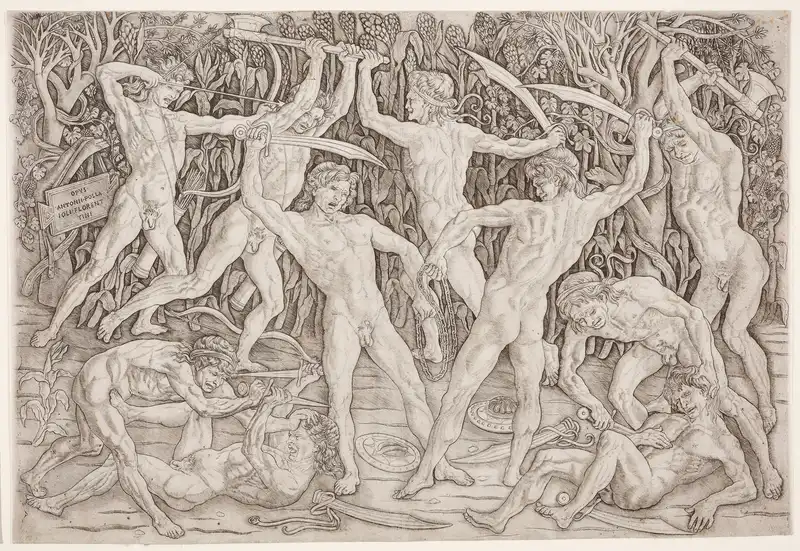

Decadent Italy

This innovative chiaroscuro woodcut by Hans Burgkmair the Elder packs a punch. The sinister figure of death is forcing a young man’s jaw apart. His horrified lover, dressed in a light, fluttering robe, tries to escape, while in the background a Venetian gondola can be seen bobbing on a canal. Hans Burgkmair demonstrates his intimate knowledge of Italian Renaissance art: the three-dimensional architecture, the drapery and clothing of the figures – everything positively screams “Italy and Roman antiquity”. But is the print also a veiled critique of the decadence of the south? The woodcut could be read as an allegory of what Venice was notorious for: sexual promiscuity and sexually transmitted, deadly syphilis.

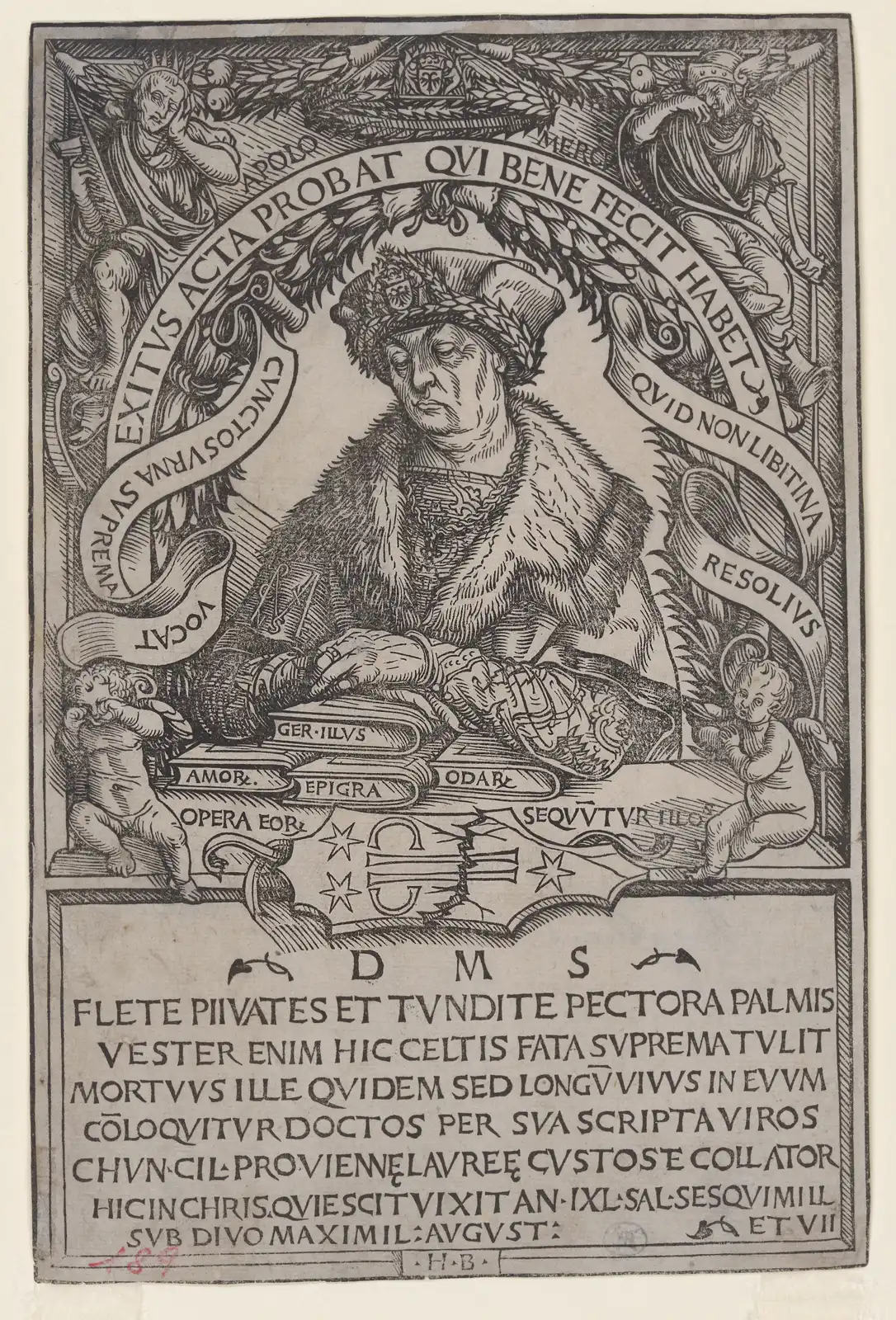

A monument on paper – Hans Burgkmair’s print was created to mark the death of the humanist Conrad Celtes (1459–1508). The scholar, who was close to Emperor Maximilian, played a decisive role in the debate about a distinct, German culture, history and identity. In the commemorative portrait, his hands are resting on one of his last works, the Germania Illustrata, an ambitious but never-completed treatise on the geography and history of the German lands.

The desire for roots: In Germany’s quest for her “own” culture, Germania, a short ethnographic text by the Roman historian Tacitus (c. 58–120 AD) played an important role. In the wake of the rediscovery of the manuscript in 1425 and in keeping with the spirit of a “Renaissance in the North”, the absurd idea began to take hold of a “pure” and homogenous original German people with supposed virtues that could now be revived.

No immigrants gave the Germanic people their origin, nor did any mishmash of people picked up here and there.

Germania and its catastrophic consequences

Tacitus had never travelled in Germany and his work had precious little to do with reality. Yet many humanists of the Northern Renaissance considered the text a valuable source. At last, the longed-for root of a “Germanic”, northern European character seemed to have come to light, older and allegedly more ‘original’ even than Roman antiquity itself, which was largely informed by the Greek culture before it. However, Tacitus deliberately distorted the facts: He turned the many scattered population groups in north-eastern Europe, who time and again managed to hold the Roman armies in check, into a cohesive, indigenous Germanic people, when they were anything but. According to Tacitus, they were autochthonous, genetically “undiluted”, beer-drinking, somewhat rough in nature, but brave, honest, combative, blond and tall. These fabrications fell on disastrously fertile ground and were to have catastrophic and murderous consequences in the long history of German nationalism – especially during the Nazi period.

Culture and politics cannot be separated: In Augsburg, too, art was put in the service of power. The extent to which the Germanic origin myth was in circulation is illustrated by the design for the mural of Augsburg’s town hall from the 1510s.

The Renaissance in northern and southern Europe was partly shaped by myths about a distant past. One such fantastical construct of origins and identity was being actively developed and promoted in Augsburg around 1500. The dubious ideas of the time continue to resonate to this day.

Next Generation -

A Son of Augsburg

Known Across Europe

4

From one generation to the next: the new forms of art developed in Augsburg continued to thrive even after the death of both Burgkmair and Holbein the Elder. The latter’s second son, Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543), rose to much greater fame and was soon known all over Europe. To this day he is admired as one of the greatest artists of the “Renaissance in the North”.

At the sight of a picture painted by Holbein [the Younger] one might be moved to exclaim: ‘Only God could have produced the marvellous work I see; no human hand could have done it.’

A Self-Assured

European

Hans Holbein the Younger grew up in the artistic circles of Augsburg. Together with his older brother Ambrosius he worked in the Holbein family business. A child prodigy with star potential – very early on his father recognised his younger son’s unusual talent and set about not just nurturing but marketing it.

In 1515, at the age of 18, Hans Holbein the Younger left Augsburg to spend his journeyman’s years working under other artists, and initially followed his brother Ambrosius to Basel. Influenced and inspired by the art of his birthplace on the Lech, he was about to embark on a stellar career.

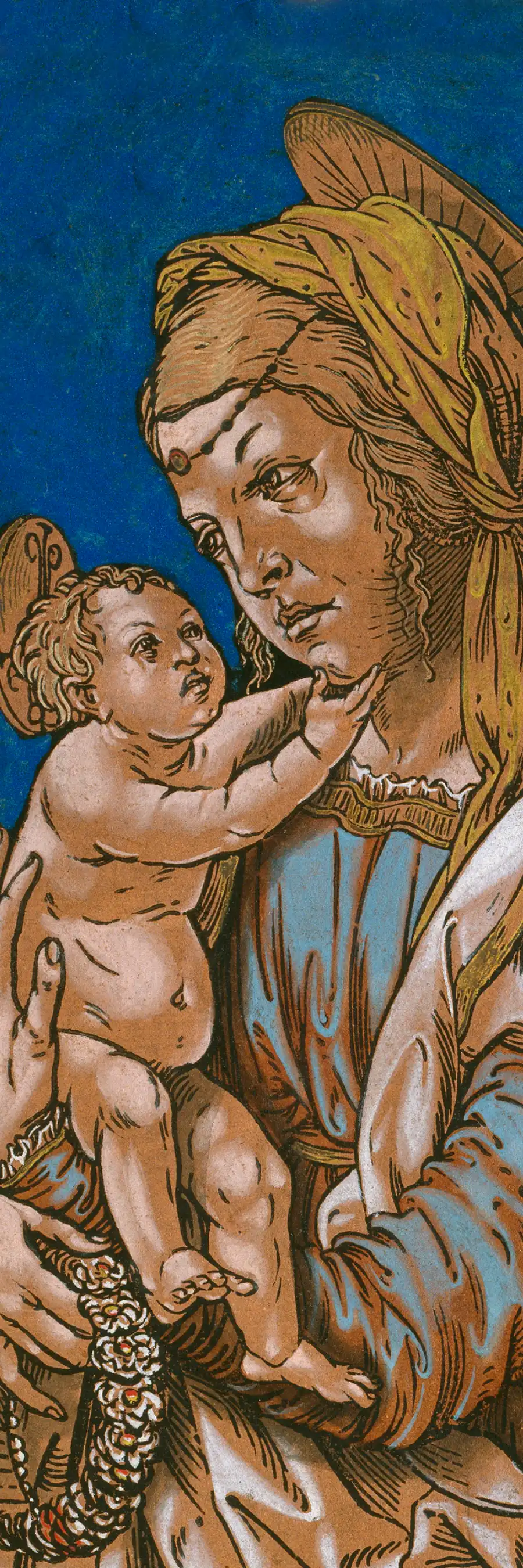

In the early years of his career in Basel, Hans Holbein the Younger continued to develop the pictorial language that had emerged in Augsburg, with northern and southern European influences – the Netherlandish tradition and the Italian Renaissance – united in vibrantly colourful paintings rich in detail! Holbein continued to deliver on the promise of his precocious talent: his pictures are highly creative and full of hidden references – as demonstrated by the Solothurn Madonna of 1522.

A painter with Europe-wide ambitions: In 1523/24, Hans Holbein the Younger travelled to France and tried to obtain a position as court painter to Francis I. Unsuccessful but inspired by the works in the French royal collection, he returned to Basel. Eventually, Holbein decided to seek employment in England. None other than Erasmus of Rotterdam recommended him to his friend, the statesman and scholar Thomas More at the glittering court of Henry VIII. Before and after his first two-year stay in England (1526–28), he painted the Madonna of Jakob Meyer zum Hasen – a masterpiece of 16th-century European art that has lost none of its power to astonish the viewer.

Your painter, my dearest Erasmus, is a wonderful artist.

In this late self-portrait, Hans Holbein the Younger describes himself as a citizen of Basel. But the artistic climate of his adopted hometown had since soured. In 1528/29, Protestant iconoclasts rampaged through the city – Martin Luther’s Reformation called for change, also with regard to the use of images in society and the role of religious art. The great flourishing of the “Renaissance in the North” was drawing to a close.

Innovative techniques, new imagery and an art that combines influences from Northern and Southern Europe. Around 1500 the artists of Augsburg produced art-works of great originality. Come and marvel at the paintings, sculptures and prints and experience the Renaissance of the North!

NEWSLETTER

Wer ihn hat,

hat mehr vom Städel

Aktuelle Ausstellungen, digitale Angebote und Veranstaltungen kompakt. Mit dem Städel E-Mail-Newsletter kommen die neuesten Informationen regelmäßig direkt zu Ihnen.

GEFÖRDERT DURCH